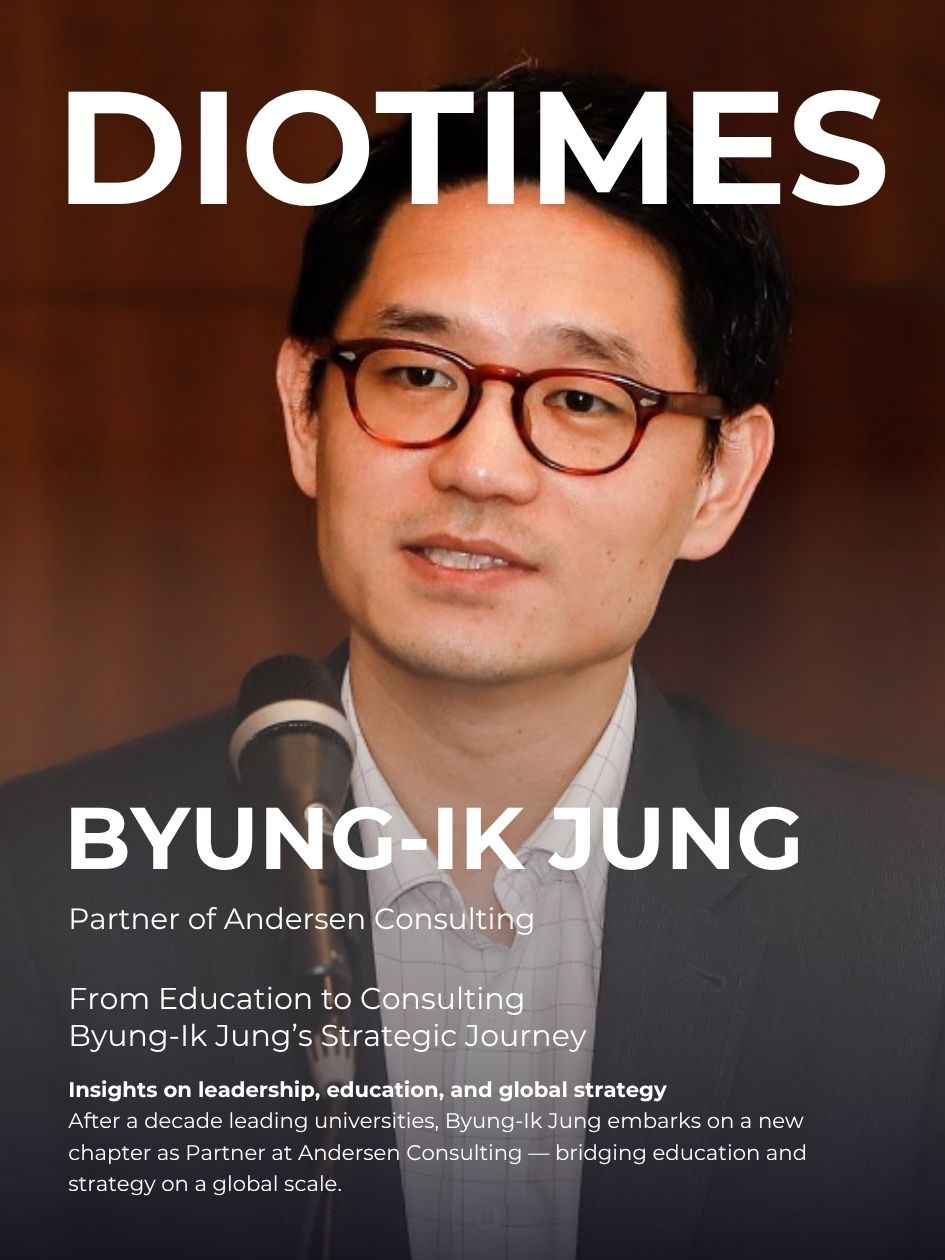

Byung-Ik Jung

Byung-Ik Jung, who has led strategy and internationalization in the education field at home and abroad, has chosen a new path. After more than a decade of driving university development as a professor and dean, he is returning to the consulting stage as a Partner at Andersen Consulting.

His consulting capabilities—honed at Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and LG Electronics’ Strategy Team—together with his administrative, strategic, and internationalization experience in higher education accumulated at SolBridge International School of Business and Busan International College (BIC) at Tongmyong University, have laid the groundwork for this next leap. In particular, his experience as the inaugural dean of BIC, where he directly established the vision and strategy for a new international college and managed the organization, became a major turning point in his career.

Going forward, he aims to serve as a bridge between education and society by providing strategic consulting to universities, international schools, local governments, and public institutions. There is growing anticipation about the synergies and new possibilities that will emerge when deep insights from the field of education meet the know-how of global strategy consulting.

In this interview, we hear about Partner Jung’s journey and his vision for the future, as well as the leadership lessons and insights gained at the intersection of education and consulting.

What led you to return to the consulting industry after finishing your term as Dean of BIC (Busan International College)?

After working as a consultant at BCG, I spent eight years at SolBridge of Woosong University as Head of Strategic Planning and Head of International Relations, which gave me the confidence that even regional universities in Korea can create leading models of internationalization. Later, as the inaugural dean of a newly established international college at Tongmyong University, I gained valuable experience building the Busan International College (BIC) brand from a zero base.

From my experience at two regional universities—Daejeon and Busan—I gained three important realizations.

First, although everyone says regional universities are difficult, precisely because of that, even a small amount of effort can produce remarkable change. Student recruitment, employment rates, faculty hiring—none of these is easy, but change is never impossible. I especially felt how outcomes can be completely different when, in addition to existing members, a small number of change-makers with problem-solving skills and execution power come together.

Second, to drive change at regional universities, it is necessary to take on areas that had not been tried before—and one of those is internationalization. Just as SolBridge elevated the brand value of Woosong University, Tongmyong University boldly put forward the city brand “Busan,” rather than “Tongmyong,” to attract international students and channeled many of them into BIC. Because international students are outside the enrollment cap, they deliver direct financial results; and from recruitment to management and employment, this is also a new area that existing staff tended to avoid. Through this process, I became convinced that internationalization can be a powerful tool for innovation at regional universities.

Third, based on these experiences, I wanted to support more universities and change at a larger scale. This includes not only regional universities but also major universities in Seoul. Indeed, since stepping out as a Partner at Andersen Consulting, I have received multiple consulting requests from international relations offices at well-known universities in Seoul. People who did not easily approach me while I was a dean at Tongmyong University now seek professional support from a global consulting firm.

Ultimately, the simple hypothesis that drew me back into consulting is this: “In some ways, regional universities are easier to transform; internationalization is the most powerful option among the levers of change; and if we can transform regional universities—though it may be harder—then we can also transform in-Seoul universities, with an even greater impact.” Is that too simple?

If my hypothesis is right, it connects to my confidence that I may be the best person to deliver such change. Through Andersen Consulting, I hope to support many universities with internationalization and a variety of strategic initiatives, contributing to the enhancement of Korean universities’ global competitiveness.

What strengths do you believe your experience in the field of education brings to consulting?

Through my time in education, I believe I have developed two key strengths.

The first is the combination of strategy and execution. At SolBridge of Woosong University, I served as Head of Strategic Planning and Head of International Relations, leading a team of more than 10 multinational staff. In this role, I was responsible not only for strategic planning but also for direct execution. At Tongmyong University, I had the opportunity to design a newly established international college from the ground up and to persuade faculty and staff accustomed to the traditional Korean system to embrace and operate a new international institution. This gave me valuable experience in change management. During my time at BCG, I carried out large-scale strategic projects for leading companies in Korea and abroad, but execution was ultimately the client’s responsibility. In contrast, at universities I experienced both strategy design and execution, which has given me a deep understanding of how academic administration and strategy truly work in practice.

The second is an understanding of the intersection between education and consulting. As a professor, I taught students, but I also conducted workshops and training programs for executives and key talent at major corporations such as Samsung, LG, SK, and Hyundai. If consulting is a task-oriented activity focused on solving specific problems and providing direction in a short period of time, education is a process of equipping a large number of people with the capacity to define and solve problems on their own. In the university environment, both approaches are necessary. At times, one must identify the problem clearly and provide answers, while at other times, it is important to enable diverse stakeholders to define and address issues themselves. Teaching both students and professionals gave me the opportunity to cultivate these abilities in a balanced way.

What turning points did your experience as Dean of BIC provide in your career?

My time as Dean of BIC gave me two major turning points in my career.

The first was the courage to step off a stable path and embrace new challenges. Looking back, my eight years at SolBridge was the longest period I stayed at one institution, and before that, the three years at LG Electronics prior to my MBA was my longest professional experience. Honestly, had I not moved to Tongmyong University, it is quite likely I would still be teaching at Woosong today. However, then-President Ho-Hwan Jeon of Tongmyong personally came to Daejeon to invite me to take on a new challenge, and in that moment I felt a renewed sense of passion and hunger for change. Relocating with my family to Busan and breaking out of a stable daily routine was not just another career move—it was a symbolic turning point that reshaped my career path. Because of that experience, I was able to conclude my one-and-a-half-year tenure as dean at Tongmyong and make an even greater leap to Andersen Consulting. Breaking the mold the first time is hard, but after that it becomes easier.

The second was that it allowed me to bring my leadership experience in academic administration to completion. Up to that point, I had achieved many results under the unconventional title of Head of Strategic Planning, but I had not fully experienced the weight and responsibility of an official position. As a dean, however, every achievement and every mistake was attributed to my name. Through this process, I was able to experience academic leadership in a conclusive and meaningful way in my 40s, and this gave me the substance and confidence to return to the consulting industry with strong foundations.

During your time at SolBridge International School of Business, what moments did you find most rewarding in leading strategic planning and international relations?

I can point to three particularly rewarding moments.

The first was launching a joint executive program with Northwestern University. Northwestern is one of the top universities in the world, and running a joint program with them is no small feat. This opportunity arose when we invited Professor Deepak Jain, former Dean of Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management and former Dean of my alma mater INSEAD, to serve as Honorary President of Woosong University. He devoted significant effort to advancing Woosong’s global strategy, and the joint program with Northwestern’s Medill School was the result of those efforts. Though operating it during COVID-19 presented many difficulties, the fact that a regional university could deliver a program alongside a top global institution was immensely rewarding.

The second was establishing a 4+1 joint program with NYU Stern School of Business. To create a pipeline from SolBridge undergraduate programs into prestigious U.S. master’s programs, I directly cold-emailed deans, associate deans, and program directors at the top 30 business schools in the U.S. This led me to meet a professor in NYU’s accounting department who had a strong interest in Korea. He informed me that linking the program to internships with Big 4 accounting firms would be essential. Leveraging my previous work at Samjong KPMG, I negotiated an MOU to secure internships for students completing the program. As a result, many students from SolBridge who joined the NYU 4+1 program went on to land jobs at leading firms such as McKinsey and PwC.

The third was setting up a SolBridge campus within FTU (Foreign Trade University), one of the top universities in Vietnam. This project began when a local staff member in Vietnam sent a cold email directly to the FTU president. Fortunately, the president had studied in Korea at Yonsei University and was very open to collaboration, so discussions advanced quickly. At the time, several U.S. universities were already operating programs on FTU’s campus, but SolBridge became the first Korean university to do so. We designed the program to follow the SolBridge curriculum fully: students would study at FTU for their first two years, then transfer to Korea for their final two, ultimately graduating with a degree from Woosong University. Thanks to FTU’s high-caliber students, the program was a great success, and its graduates secured positions at firms such as McKinsey and BCG in Vietnam. This elevated the standing of both SolBridge and Woosong University in the Vietnamese market.

These three experiences were especially meaningful to me because they showed that SolBridge was not confined to its region but was truly able to rise onto the global stage.

As the inaugural dean of Busan International College at Tongmyong University, what was the most difficult challenge and how did you overcome it?

The most difficult challenge I faced as the first dean of BIC was establishing “One College, One Culture.” At the time, most of the faculty were Korean, and operations were conducted primarily in Korean. As a result, foreign faculty members were relegated to teaching a few English liberal arts courses and remained peripheral. Under such a structure, it was impossible to become a true international college.

To change this, I first set out to reform liberal arts education. Reforming major courses faced strong resistance from Korean faculty, so I decided from the beginning to bring in foreign professors as change agents for BIC’s innovation. I restructured the traditional literature-, history-, and philosophy-centered liberal arts courses into competency-based Core Innovation Courses (CIC) such as Critical & Creative Thinking, Global Leadership, and Cross-Cultural Communication. We carefully selected participating faculty, organized teaching workshops to upgrade their teaching skills, and collaborated with external consulting firms to co-develop textbooks. As a result, CIC became BIC’s flagship program embodying its core value of “Teaching Innovation.” Foreign professors rose to become the main drivers of these courses, and their presence grew naturally stronger.

We also began holding monthly faculty meetings in English and adopted English as the official language of the college. Emails and even building signage were switched to English. As these changes were implemented, a culture of open discussion emerged, and foreign faculty increasingly spoke up and took leadership in conversations. The transformation of language and curriculum ultimately drove a transformation in organizational culture.

In your view, what role do the two keywords—internationalization and strategic planning—play in the development of educational institutions?

Today, internationalization is no longer an option but a mandatory strategic task for universities. It is not only a survival strategy for regional universities but also a core area that even top-tier universities in Seoul view as crucial to their future competitiveness. Yet many universities still narrowly interpret internationalization as simply increasing the number of international students, which misses its essence. Successful internationalization strategies go beyond student recruitment; they act as a trigger for transforming a university’s brand, academic standing, organizational culture, financial structure, and global partnerships.

For example, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (APU) in Japan clearly shows how internationalization can redefine a university’s identity and positioning. From its inception, APU recruited more than half of its students and faculty from abroad, operated an English-centered curriculum, and built a collaborative ecosystem with global companies and institutions. As a result, it didn’t just increase its international student population—it transformed itself into a “global innovation hub,” elevating its institutional brand to the next level.

Internationalization also carries another critical value: organizational and cultural innovation. A diverse community of international students and faculty puts pressure on universities to digitalize administrative systems, provide English-based administrative services, and adopt transparent performance management aligned with global standards. These changes directly impact rankings, finances, and research networks, ultimately redefining the university’s competitiveness.

Strategic planning is another area where universities will need the most transformative change. Most universities have a “planning office,” but in practice, their operations differ fundamentally from the strategic planning departments of corporations. The biggest reason is that university planning is conducted within the boundaries of regulations and guidelines set by the Ministry of Education. This results in standardized mid- to long-term plans, since universities must align their visions with government evaluation criteria and funding requirements.

If you read the vision statements and development plans of many universities, you often encounter repeated phrases such as “nurturing global talent,” “strengthening industry-academic cooperation,” or “responding to the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Without the university’s name attached, it is difficult to tell which institution the document belongs to. This stands in stark contrast to corporations, which develop strategies to secure differentiated positioning and sustainable competitive advantage. In higher education, strategy too often becomes evaluation-driven and focused on short-term performance.

Going forward, however, the environment surrounding universities will change rapidly. Declining student populations, the expansion of online degrees, intensifying competition among global campuses, and AI-driven personalized education will make it impossible to survive with policy-driven planning alone. Universities, like corporations, must adopt market- and demand-oriented strategic planning capabilities. This includes data-driven decision-making, attracting private investment, and expanding global partnerships—innovative planning models that will be indispensable.

What major projects or goals will you take on as Partner at Andersen Consulting?

First, I would like to highlight university consulting. At Andersen Consulting, I intend to focus on solving the complex challenges faced by university presidents and board chairs. With my background as a consultant at KPMG and BCG and over a decade as a university professor, I have acquired both consulting expertise and a deep understanding of the realities of higher education. In many other consulting firms, when a university project is commissioned, partners or consultants from unrelated fields such as IT or finance are often assigned. Andersen Consulting takes a different approach. As a Partner, I bring both consulting and university management experience, and we will also deploy consultants with relevant expertise to deliver realistic and actionable solutions.

The main areas I will focus on include:

Developing internationalization strategies and recruiting international students

Strategies for overseas expansion, such as franchise campuses

Mid- to long-term vision and strategy roadmaps for universities

University ranking and accreditation strategies

Identifying and pursuing revenue-generating projects such as real estate development

Advising on university closure, mergers, and acquisitions (M&A)

Departmental restructuring

Employment and entrepreneurship strategies

Faculty and staff performance evaluation and HR system innovation

Digital transformation strategies, including AI integration

Ultimately, my goal is to become the partner who understands universities most deeply, delivering tangible solutions, and building lifelong partnerships rather than one-off projects.

Additionally, strategic projects are also coming in from international schools and foreign schools, as well as from local governments and public institutions. Universities, other educational institutions, and municipalities share many similarities: they operate in regulation-driven environments, they have strong public-service elements, and they are typically focused on local business. At the same time, such clients often have strong interest in overseas cases and global strategies. Through Andersen Consulting’s global network and expert pool, we can provide global insights and best practices from leading institutions abroad—something local consulting firms struggle to deliver. While universities will remain my core focus, Andersen Consulting will grow into a global management consulting firm that also encompasses international schools, municipalities, and public institutions.

How will your experience at BCG and LG Electronics’ Strategy Team connect to this new role?

Working in consulting and in a corporate strategy team contributes in two main ways.

First, adopting corporate thinking and methods of working in the university sector creates significant advantages. I now provide consulting for universities, local governments, and public institutions, and my dual experience with both public-sector logic and corporate ways of working is a clear differentiator. These two domains may seem like oil and water—difficult to mix—but having spent about a decade in each, I have developed the ability to think and work from perspectives that others may not.

Second, my networks are invaluable assets. BCG, LG Electronics’ Strategy Team, my INSEAD MBA, my IE alumni community, Seoul National University alumni, high school alumni, and Air Force officer alumni—all form a robust network. In consulting, sometimes “who you know” matters more than “what you know.” When we need to find a subject-matter expert in a specialized area, I can always rely on my senior, junior, and peer networks to connect us to the right people.

What do you see as your differentiated strengths in providing strategic consulting for educational institutions, local governments, and public agencies going forward?

As a Partner at Andersen Consulting, our team’s strengths fall into three main areas.

First, execution-driven solutions. Many consulting projects end at the stage of a written report or strategic proposal. Our team goes beyond “paper strategy” to present a concrete execution roadmap—and, when needed, we directly support implementation. For example, when we craft a university internationalization strategy, we don’t stop at recommendations for recruiting international students. We leverage our overseas university network to sign partnership agreements and even support the initial student recruitment, providing true end-to-end assistance. This approach lets clients see consulting outcomes translate immediately into tangible results.

Second, deep partner involvement with industry experience from start to finish. One of Andersen Consulting’s biggest differentiators is that partners with domain expertise stay deeply engaged throughout the entire project. I personally have over a decade of on-the-ground experience in university strategy and internationalization, and partners at Andersen—myself included—lead from initial diagnosis through strategy design and execution. The result is not desk-bound theory but solutions that can be applied immediately in the field, allowing clients to feel both expertise and practicality throughout the engagement.

Third, building long-term relationships rather than one-off projects. We don’t treat projects as one-time contracts. We aim to build partnerships that last five, ten years or more. For instance, if the first project is a university’s mid- to long-term strategy, we follow through with subsequent initiatives—internationalization, industry–academia collaboration, revenue diversification, digital transformation—serving as a full life-cycle growth partner. In this way, the client gains not just a “consulting provider” but a true companion to the organization, while we accumulate results together over the client’s growth journey.

What is the most memorable leadership lesson you’ve gained from the global education field?

Working in universities has given me the chance to meet many presidents and deans. What I learned from meeting outstanding leaders is that the more renowned and accomplished they are, the more humble, down-to-earth, and relationship-oriented they tend to be.

At Woosong University, we invited Professor Deepak Jain—former dean of INSEAD, where I studied—to serve as honorary president. He leads with a warm smile and inclusive presence. During student forums, he would ask each student’s name, write every name down, memorize them, and call them by name. He never missed that habit in meetings, and he always sent people off with a full embrace. Calling a student by name and giving a hug often communicates more than a few words of advice.

Salvador Carmona, the president of IE Business School where I did my doctoral studies, treasures relationships and communicates with exceptional care. He replies to emails within a day, arrives ten minutes early to meetings, checks in via WhatsApp when disasters occur in Korea, and brings small gifts when he visits. Contrary to my assumption that the busiest global leaders might neglect relationships, the best leaders I met were outstanding at caring for people—and that quality did not change even as their status and fame rose.

Now in my mid-40s, I try to care for everyone and remain humble, just like the remarkable mentors I’ve met. I realized that greatness does not come from title or rank. If anything, people are great because they are humble.

What does Korea’s education sector most need in order to raise its international competitiveness?

I believe two changes are essential.

First, active utilization of leaders with global experience. At SolBridge, we appointed deans from the U.S. and France, and Woosong accelerated globalization by having President John Endicott lead the university for over a decade. English was the official working language at SolBridge; there was no discrimination between Korean and international staff; and absent regulatory constraints, operations followed global standards. Korean companies adopted global standards long ago, but universities remain conservative, seniority-based, and risk-averse. It’s time to boldly bring in globally seasoned leaders and change the culture first.

Second, bring in corporate talent and adopt performance-based systems. Woosong proactively appointed leaders from industry to key posts. Hwang Woon-Kwang, former LG Electronics vice president (now president of Daelim University), served as SolBridge’s vice president, and appointing me—then in my 30s—as head of strategic planning at SolBridge was also a bold move. Sejong University appointed leaders from Samsung Economic Research Institute and CJ as business school deans; Kwangwoon University picked a partner from a global consulting firm to head a major institute. Step-pay scales, seniority, and a culture of self-protection are holding universities back. I’m not arguing to deny existing systems wholesale; rather, in new domains such as internationalization and new ventures, universities should decisively introduce performance-based models. When a late-20s Samsung hire starts at over 60 million KRW while a late-30s professor with a completed PhD also starts at around 60 million, it’s hard to attract top talent to academia. Where should we begin? Every university has a step-pay table. In extreme cases, a candidate with a Nature/Science paper and one with only KCI-level papers start on the same salary. Is that desirable? We need flexible compensation and performance evaluation systems that reflect individual capability—and, further, as Taejae University did, we might even pilot eliminating tenure in selected departments as a starting point for change.

Where can “Korean-style leadership” or Korean experience create value in the global consulting market?

A recent LinkedIn post caught my eye: news of Korean deans taking positions in places considered higher-education powerhouses—the U.S., U.K., Singapore, and Hong Kong. Such cases remain rare. Among leading MBA schools in the U.S. and Europe, most deans are American, European, or Indian; it’s still uncommon to find Korean, Chinese, or Japanese deans. The same goes for senior leadership in Silicon Valley’s global firms.

I see two reasons. First, a gap in creative problem-solving. Korean elites excel at solving well-defined problems, but often hesitate when facing open-ended ones—this can limit global leadership competitiveness. Second, small-talk capability. To thrive in Silicon Valley, you need to build broad, loose networks through small talk. Expertise alone has limits; creative solutions to complex problems emerge when diverse intellectual networks intersect. Many Koreans are relatively less adept at cultivating such networks.

Where, then, does Korean leadership create distinctive value globally? I find it in relationship-oriented thinking—jeong (affectionate bond) and loyalty. Some joke that Korean leaders “read the room” for their teams, but I see this as a strength: employees are internal customers, and an internal-customer-centric leadership style can inspire commitment and collaboration. If small talk creates wide but shallow ties, jeong and loyalty build narrower but deeper ones. Unlike efficiency- and task-centric Western styles, Korean leadership emphasizes relationships and community values. Combined with the growing need for inclusive leadership worldwide, this relational strength can become a true differentiator for Korean leadership.

Looking back on your 10 years as a professor, is there a student or project that stands out most in your memory?

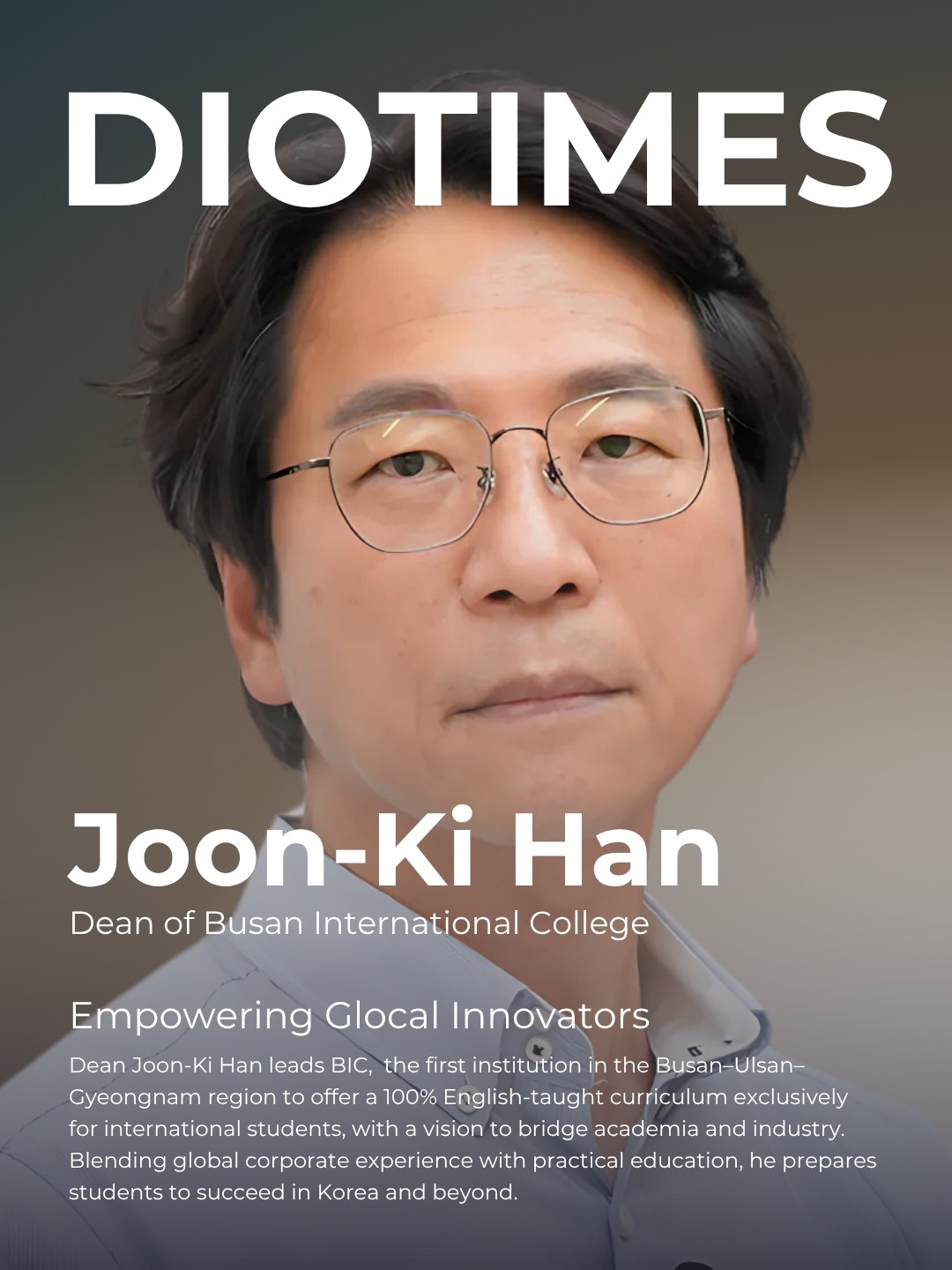

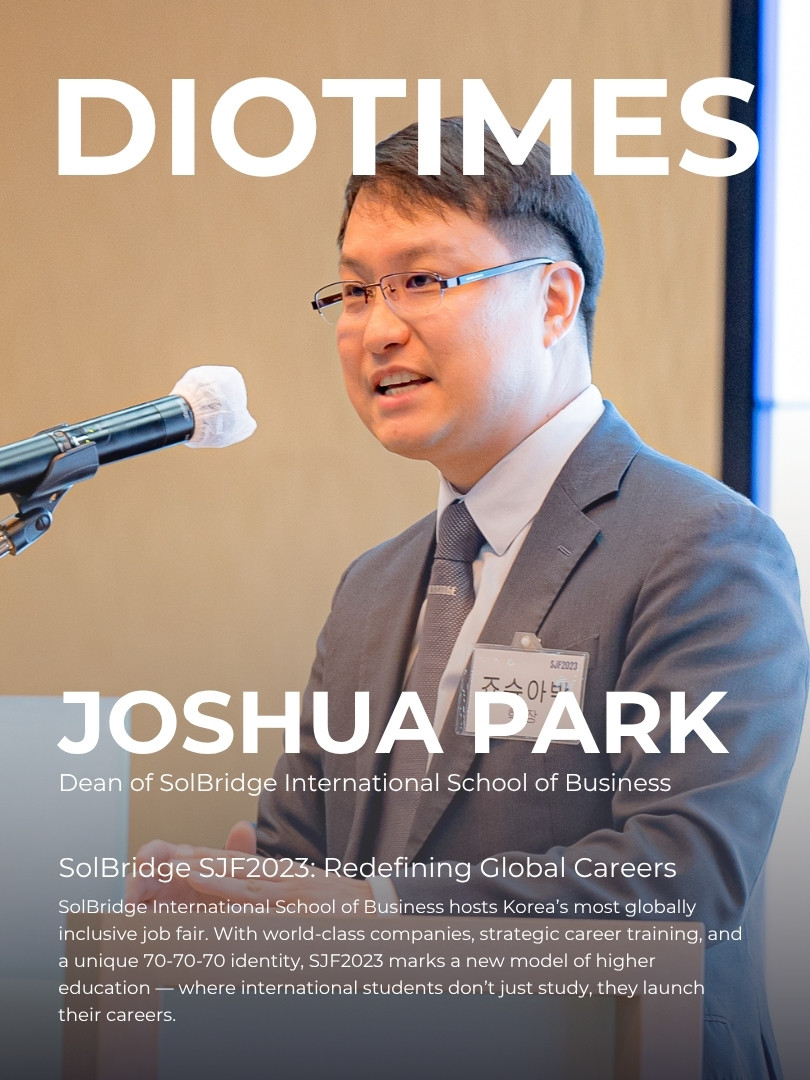

First, what gives me the greatest sense of pride is that all of my colleagues grew personally and professionally during that time. Not long ago, the head of a Korean higher education consulting firm remarked to me, “It seems that SolBridge alumni are active in internationalization efforts across the sector.” Indeed, many colleagues, seniors, and juniors with whom I worked are now making significant contributions worldwide as SolBridge graduates. Joshua Park is working at George Mason University Korea, Dean Joon-Ki Han now leads Busan International College, Iskandar—who worked with me for seven years—has returned to Uzbekistan and now serves as the head of a foundation overseeing three universities, Rodrigo is teaching at a top business school in Portugal, and Professor Koo In-Hyuk is teaching entrepreneurship at Sookmyung Women’s University. Seeing former colleagues open new chapters for their institutions worldwide gives me both pride and powerful motivation.

Second, I had the opportunity to write several books on design thinking, appear on EBS and other broadcasts, and lecture at leading companies. Before becoming a professor, I never imagined I would give talks at Samsung, LG, SK, Hyundai Card, and other major corporations. Yet as a former strategy consultant, my research and publications on design thinking positioned me as a sought-after speaker on logical thinking, design thinking, and integrated problem-solving capabilities. What began as a modest goal to share my experiences with a small readership grew much larger. Once my books were published, many people I had never met began to seek me out. Looking back, I am deeply grateful for the role “design thinking” played in strengthening my professional trajectory.

As you embark on this new chapter, what excites you most on a personal level?

At Woosong and Tongmyong, I was limited in my ability to support other universities. Now, as a Partner at Andersen Consulting, every university in Korea can potentially become my client. Fundamentally, I want to advise and consult with Korea’s top-tier institutions—Seoul National, Yonsei, Korea University, KAIST, and others. With universities nationwide in crisis and in urgent need of transformation, top institutions in particular must strive to achieve not just national or regional prominence but truly global standing. Yet such transformation is difficult for universities to pursue on their own. As an external consultant, I aim to leverage my experience and Andersen Consulting’s global network to help Korea’s leading universities attempt bold new strategies and innovations.

Looking five years ahead, what is your vision?

I recently attended a Korea Times conference on “Strengthening the Global Competitiveness of Korean Universities.” The core message was clear: despite Korea’s economic strength and cultural influence through K-culture, our universities lag in global competitiveness. The call was for increased international student recruitment, stronger research output, and improved QS rankings. While overdue, I am encouraged that such discussions are now taking place. My vision is to support multiple universities through consulting and advisory services to raise the global competitiveness of Korean higher education.

Second, I hope to see the emergence of a world-class business school in Korea, comparable to IE, INSEAD, or LBS. Comprehensive universities like Seoul National, Yonsei, and Korea University are not ideally positioned to cultivate highly specialized business schools of this kind. Just as the founder of Hanssem created Taije University, I believe a visionary leader could establish a standalone, globally competitive management school in Korea and for Asia. If such a leader emerges, I would like to support them. Even if not immediately, I am confident that there are entrepreneurs, educators, and leaders who share this vision. My role will be to help lay the foundation so that one day Korea can boast a business school that stands among the best in the world.